Orange Mold: Complete Identification & Safe Removal Guide

🚨 Is orange mold dangerous to health?

Yes, orange mold can be dangerous, particularly for immunocompromised individuals, children under 12, and people with existing respiratory conditions. Species like Acremonium strictum cause invasive infections, while Aspergillus flavus produces carcinogenic aflatoxins. Professional removal is required for areas exceeding 1 square meter per Health Canada guidelines.

📋 TL;DR – Orange Mold Essentials

⚠️ Health Risks

- Allergies and respiratory issues

- Serious infections in vulnerable populations

- Carcinogenic aflatoxin exposure

🔍 Identification

- Fuzzy texture with musty odor

- Orange/yellow coloration

- Grows on organic materials

🏠 Common Locations

- Bathrooms and wooden surfaces

- Basements and kitchens

- Food storage areas

🛡️ Safe Removal

- DIY for areas under 1m²

- Professional removal for larger infestations

- Control humidity (30-50%)

🆓 Concerned About Orange Mold? Get a Free Inspection!

Orange mold can pose hidden hazards in your home, often found in damp areas and posing health risks. Don’t let it go unchecked! Contact Mold Busters for a free virtual mold inspection. Our experts will provide a comprehensive assessment and a plan to tackle any mold issues, ensuring your home is safe and healthy.

What is Orange Mold?

Orange mold is a common term for various filamentous fungi and fungi-like organisms that appear orange in color. These organisms typically grow in dark, moist environments and play crucial ecological roles in decomposing organic matter.

Understanding orange mold identification is crucial for Ontario and Quebec homeowners, where humid conditions during spring snowmelt and summer months create ideal growth environments. These organisms typically grow in dark, moist environments but can also be found on deadwood, forest soil, conifer cones, and food items.

Figure 1. Orange mold in basement showing characteristic fuzzy texture and orange coloration (Photo source: Mold Busters).

🌿 What role does orange mold play in nature and indoor environments?

🌱 Natural Role

- Saprophytic organisms: Feed on decaying organic matter

- Ecosystem pillars: Essential for biosphere function

- Lignocellulose degradation: Only organisms capable of breaking down wood structure

🏠 Indoor Impact

- Building materials: Targets cellulose-rich materials like wood framing

- Personal belongings: Affects paper products and natural fiber textiles

- Early detection crucial: Moisture control essential for property protection

All plants, especially trees, consist of sugars cellulose and hemicellulose encased in lignin. This structure provides strength and rigidity to plants while protecting water and sugars from herbivores. Consequently, fungi remain the only organisms capable of breaking down lignin and making sugars available for digestion. Since lignocellulose represents the most abundant organic material on Earth, without saprophytes the world would quickly become uninhabitable due to plant debris accumulation.

Orange Mold vs Other Substances: How to Distinguish Real Mold

True orange mold exhibits specific characteristics that distinguish it from harmless substances: fuzzy, velvety texture that appears three-dimensional, distinct musty odor, and easy transfer when touched with a cotton swab.

Many homeowners misidentify orange mold, confusing it with rust stains, mineral deposits, or food stains. Accurate identification prevents unnecessary panic while ensuring genuine mold problems receive appropriate attention.

✅ Orange Mold Characteristics

- Texture: Fuzzy, cotton-like or velvety

- Odor: Distinct musty, earthy smell

- Growth pattern: Irregular patches or colonies

- Surface type: Appears on organic materials (wood, paper, fabric)

- Conditions: Thrives in humid conditions (60%+ humidity)

- Structure: Three-dimensional growth structure

❌ Common Orange Look-Alikes

- Rust stains: Flat, metallic appearance on metal surfaces

- Mineral deposits (efflorescence): Crystalline, chalky structure on concrete

- Food stains: Sticky, easily cleanable with soap and water

- Wood stain/discoloration: Uniform color, follows wood grain patterns

- Paint discoloration: Smooth surface, no texture variation

Additionally, orange mold typically appears in areas with persistent moisture problems, while stains and discoloration occur from one-time spills or exposure events. Professional testing through air quality testing provides definitive identification when visual assessment remains uncertain.

What Causes Orange Mold to Grow: Understanding Growth Triggers

Orange mold growth requires three essential conditions: moisture levels exceeding 60% relative humidity, organic food sources, and temperatures between 15-30°C (59-86°F).

💧 Moisture Sources (Primary Trigger)

- Plumbing leaks: Most common indoor source

- Roof penetrations: Ice dams and seasonal damage

- Basement water intrusion: Spring snowmelt issues

- Poor ventilation: Condensation from inadequate airflow

🍽️ Organic Food Sources

- Wood framing: Cellulose-rich building materials

- Paper products: Books, documents, cardboard

- Natural fiber carpets: Wool and cotton materials

- Dust accumulation: Microscopic organic debris

🌡️ Environmental Conditions

- Temperature range: 15-30°C (59-86°F) optimal

- Humidity levels: 60%+ relative humidity required

- Air circulation: Stagnant air promotes growth

- Seasonal factors: Spring snowmelt and summer humidity spikes

🏠 High-Risk Areas

- Bathrooms: Without proper exhaust fans

- Crawl spaces: Unventilated storage areas

- Kitchen areas: Cooking and dishwashing moisture

- Laundry rooms: Dryer and washing machine humidity

In Canadian homes, spring snowmelt and summer humidity spikes create seasonal risk periods requiring enhanced monitoring. Poor ventilation compounds moisture problems by preventing air circulation and humidity control.

Addressing underlying moisture control issues prevents recurrence and protects long-term property value while maintaining healthy indoor air quality standards.

Types of Orange Mold Species: Common Varieties and Characteristics

Orange molds encompass two groups: filamentous fungi (true molds) that are saprophytic or plant pathogens, and slime molds (Myxomycetes) belonging to kingdom Protista with different biology and lifecycle.

What we colloquially call orange molds encompasses two similar-looking groups of organisms, but morphologically, physiologically, and genetically very divergent. Understanding these differences helps in proper identification and treatment approaches.

Figure 2. Orange mold infestation in bathroom demonstrating typical growth patterns on tile and grout (Photo source: Mold Busters).

🦠 The True Orange Mold Species

🔬 Acremonium strictum – Common Indoor Orange Mold

Acremonium strictum belongs to a group of saprophytic and opportunistic molds which causes hyalohyphomycosis – invasive infections by fungi without dark pigments. It is widespread fungus found in soil, plant debris, and rotting mushrooms.

The colonies formed by A. strictum can be orange, pink, yellow, and thus is sometimes referred to as “orange mold”. Indoors, A. strictum is often found on moist, cellulose-based construction materials characterized by predominantly humid conditions.

🟠 Epicoccum nigrum – The Allergenic Orange Mold

Epicoccum nigrum is an asexual, pigment-producing saprophytic fungus, which can infect plants, and cause allergies in humans. E. nigrum produces a variety of biomedically and industrially important molecules, including carotenoid pigments (yellow, red, and orange colors).

Figure 4. Orange Epicoccum nigrum growing on the puffball mushroom Lycoperdon pyriforme (Photo source: Walt Sturgeon, Wikimedia).

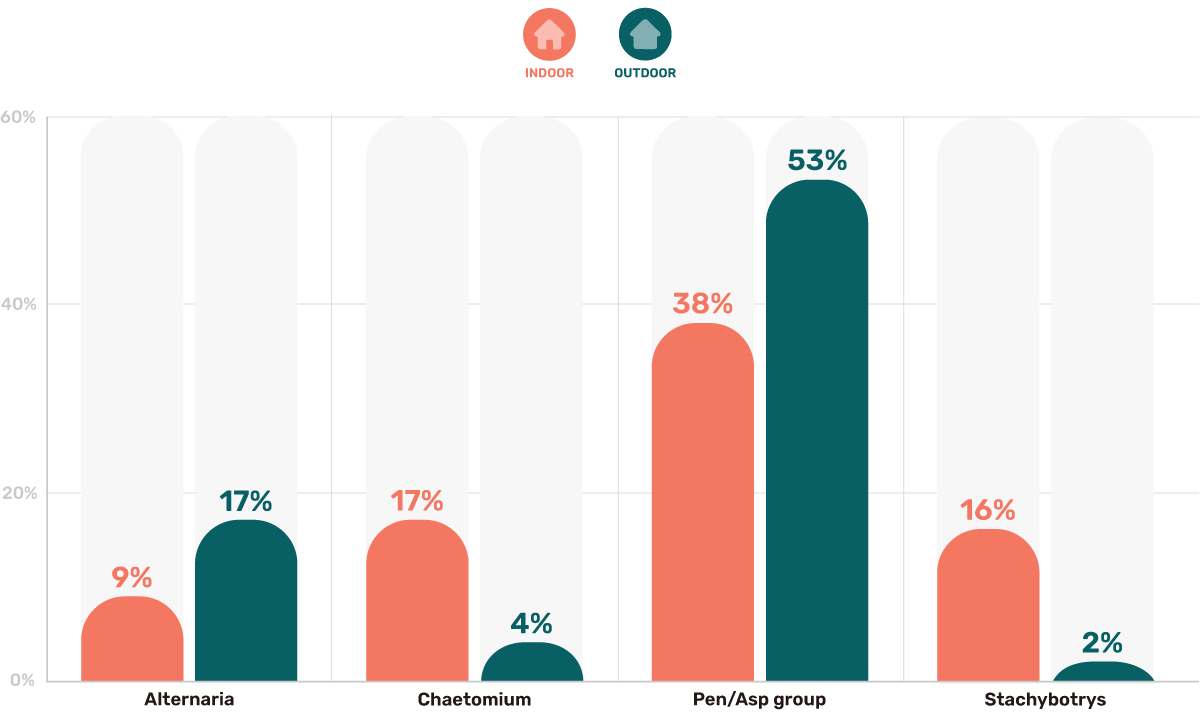

🔬 Aspergillus – The Most Common Indoor Orange Mold

Aspergillus molds are amongst the most widespread mold species, globally. They can reproduce at elevated temperatures and low water availability, which makes them one of the most widespread agents of spoilage in the world.

Figure 5. Most common toxic mold types found indoors and outdoors, ordered by presence (Source: Mold Busters Mold Stats).

☠️ Aspergillus flavus – The Dangerous Orange Mold

EXTREME HEALTH RISK: Aspergillus flavus produces aflatoxins, some of the most potent naturally occurring carcinogens. Immediate professional removal is essential.

Aspergillus flavus colonies can sometimes appear orange-yellow. This mold is most certainly unsafe to have in the household as it is one of the several mycotoxin-producing aspergilli. These toxins, especially aflatoxin B1 and B2 can cause acute liver damage, liver cirrhosis, and are known for their immunosuppressive and carcinogenic properties.

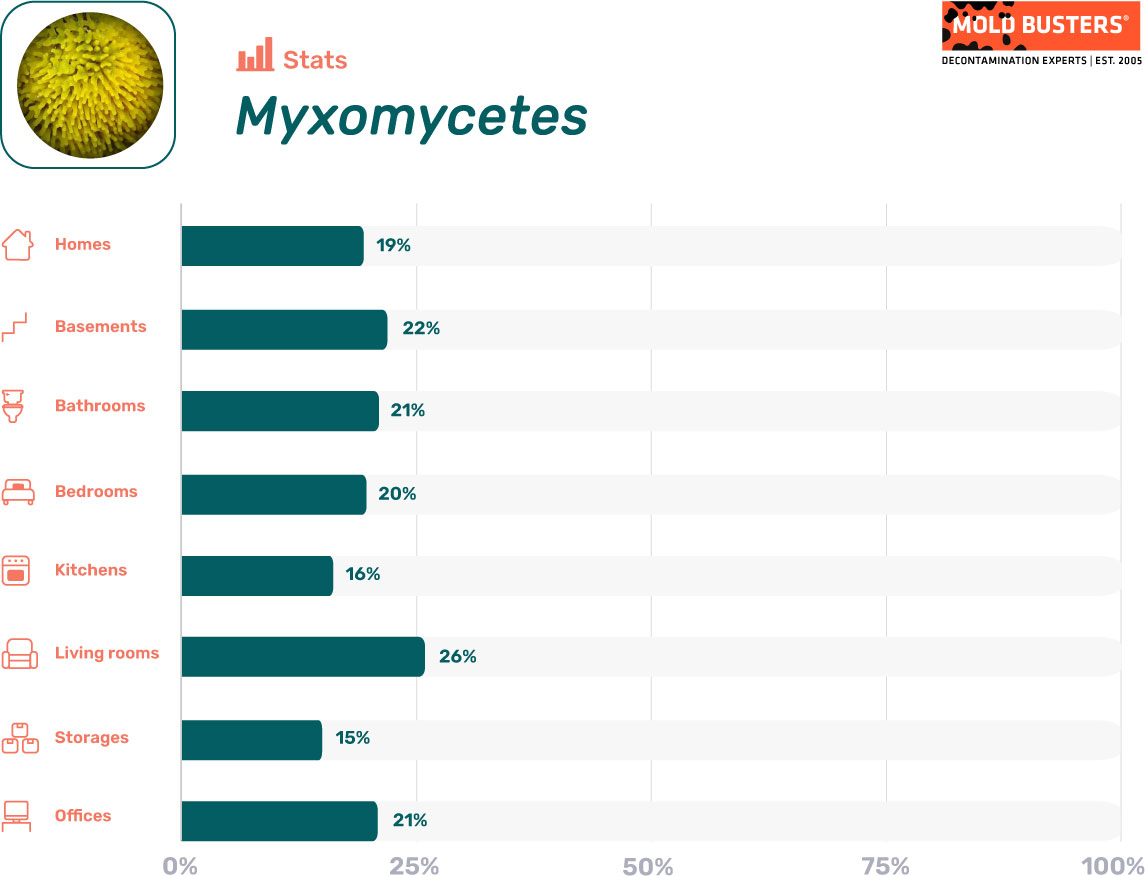

🟡 Orange Slime Mold (Myxomycetes)

🧪 Slime Molds – Not Quite Fungi

Slime molds are not quite fungi, nor primitive microscopic animals, which reflects their unique lifestyle. The majority of the time, these organisms exist as ameboid (myxamoeba) or sperm-like (myxoflagellate) active cells that actively hunt for bacteria and anything smaller than their size.

Figure 6. Orange mold on the toilet (Photo source: Mold Busters).

When autumn and cold weather comes, these cells aggregate and eventually form a plasmodium – one of the two macroscopic structures. In this form, slime mold spreads over a surface, much like a regular mold does, and starts feeding. However, unlike fungal molds which permeate the substrate and extract nutrients, slime molds feed on organic matter, bacteria, protists, other molds, and even higher fungi that are found on the substrate surface.

Figure 7. Fuligo septica plasmodium (Photo source: Stephan D66, Wikimedia).

Some of the more common slime molds that can appear orange are Fuligo septica, Tubifera ferruginosa, species from the Trichia genus. Physarum polycephalum can also appear orange when old.

Figure 8. Orange slime molds (Photo source: D. Sadikovic, Mold Busters).

🤧 Allergy Impact: Although slime molds are not classified as human pathogens like regular molds, studies show that 40% of subjects who suffer from seasonal allergic rhinitis had positive skin test reactions to slime mold spores. Statistics show that slime molds can make up to 25% of mold presence in our homes.

Figure 9. Frequencies of appearances of Myxomycetes molds in the indoor environment (Source: Mold Busters Mold Stats).

🍁 Canadian Climate Factors

Orange mold growth in Ontario and Quebec homes is particularly problematic due to seasonal climate patterns that create ideal growth conditions.

🌨️ Spring Challenges

- Snowmelt increases: Basement moisture levels rise dramatically

- Ice dam formation: Water infiltration in attics and walls

- Foundation stress: Freeze-thaw cycles create entry points

☀️ Summer Conditions

- Humidity peaks: 70%+ in Toronto creates ideal growth conditions

- Temperature fluctuations: Condensation in poorly insulated areas

- HVAC strain: Air conditioning condensation issues

Knowing this, you should be especially vigilant about orange mold growth in areas of your home with high humidity and lots of wood, particularly during the humid months from May to September.

Where Can Orange Mold Appear in Your Home?

Wooden window sills are magnets for orange mold, as well as exposed structural beams in basements. Attics are also havens for orange mold growth because they collect warm air and moisture.

🚿 Bathroom Locations

- Shower walls and tile grout: High humidity areas

- Wooden vanities and cabinets: Moisture damage from plumbing

- Ceiling areas above bathtubs: Steam condensation

- Window sills and frames: Condensation collection points

🍳 Kitchen Locations

- Wooden floors and cabinets: Cooking moisture exposure

- Ceiling above stove areas: Grease and steam buildup

- Under-sink areas: Plumbing leaks and condensation

- Backsplash and wall areas: Food preparation moisture

🏠 Basement Locations

- Exposed wooden beams and joists: Direct moisture contact

- Foundation walls: Water intrusion and condensation

- Storage areas: Poor ventilation and humidity buildup

- Laundry room areas: Washer and dryer moisture

🏠 Attic Locations

- Roof rafters and decking: Roof leak damage

- Insulation contact areas: Moisture trapped in insulation

- Roof penetrations: Chimney, vent, and skylight areas

- Poorly ventilated storage: Stagnant air pockets

Your kitchen is a hotbed for orange mold growth; wood in the floor and especially in the ceiling above the stove are vulnerable to orange mold growth. If you’re in Montreal or Ottawa, our team can help you identify and address these issues.

Figure 10. Kitchen wall infestation of orange mold (Photo source: Mold Busters).

Is Orange Mold Dangerous to Health: Understanding Toxicity Levels

Orange mold poses significant health risks that vary based on species, exposure duration, and individual susceptibility. Unlike common misconceptions that associate danger only with black mold, several orange mold species produce potent toxins.

⚠️ Most Dangerous Orange Mold Varieties

- Aspergillus flavus: Produces aflatoxins—among the most carcinogenic substances found in nature

- Acremonium strictum: Causes invasive hyalohyphomycosis, leading to infections in lungs, bones, heart, and brain membranes

- Epicoccum nigrum: Triggers severe allergic reactions and hypersensitivity pneumonitis

Aspergillus flavus represents the most dangerous orange mold variety, producing aflatoxins that cause acute liver damage, cirrhosis, and immune system suppression with even minimal exposure. Children, elderly individuals, and immunocompromised people face elevated risks requiring immediate remediation.

Exposure symptoms range from mild respiratory irritation to serious systemic reactions. Early symptoms include persistent coughing, wheezing, throat irritation, and skin rashes. Severe cases develop chest tightness, chronic fatigue, and neurological symptoms requiring immediate medical attention and professional mold remediation services.

⚡ What are the immediate symptoms of orange mold exposure?

Orange mold exposure produces recognizable symptoms that typically appear within hours to days of contact. Understanding these warning signs enables early intervention and prevents progression to serious health complications.

Respiratory Symptoms

- Persistent coughing: Dry or productive coughs

- Breathing difficulties: Wheezing and shortness of breath

- Chest problems: Tightness and discomfort

- Throat issues: Irritation and scratchiness

- Sinus problems: Congestion and pressure

🤧 Allergic and Skin Reactions

- Nasal symptoms: Sneezing fits and runny nose

- Eye irritation: Watery, itchy, or burning eyes

- Skin reactions: Rashes and contact dermatitis

- Post-nasal drip: Mucus buildup and drainage

- Neurological: Headaches and sinus pain

🚨 Vulnerable Populations at Higher Risk

- Children under 12: Developing immune systems

- Adults over 65: Weakened immunity with age

- Pregnant women: Increased sensitivity and fetal risks

- Immunocompromised individuals: Existing health conditions

These groups require immediate medical evaluation when orange mold exposure occurs, as complications can develop rapidly.

⚠️ Severe Health Complications

🔬 Medical Conditions

- Hypersensitivity pneumonitis: Lung inflammation from immune response

- Invasive fungal infections: Life-threatening in immunocompromised individuals

- Mycotoxin poisoning: From Aspergillus species exposure

- Neurological symptoms: Chronic fatigue and cognitive issues

📊 Risk Factors

- Type of mold: Not all species harmful, but identification crucial

- Severity of infestation: Large areas pose greater risks

- Length of exposure: Chronic exposure more dangerous

- Individual health: Pre-existing conditions increase vulnerability

If you experience persistent symptoms after discovering orange mold in your home, consult healthcare providers immediately while arranging professional mold inspection and remediation services to eliminate the source.

When to Call Professionals vs. DIY Orange Mold Removal

🚨 Professional Removal Required When:

- Area coverage: Mold covers more than 1 square meter (Health Canada guideline)

- HVAC involvement: Mold found in systems or ductwork

- Contamination source: Sewage or contaminated water caused the mold

- Health concerns: Anyone in home has compromised immunity

- Recurrence: Mold returns after DIY cleaning attempts

- Persistent odors: Strong musty smells even when mold isn’t visible

🛠️ DIY Orange Mold Removal (Small Areas Only)

If you notice small mold colonies in your home (less than 1 square meter), you can usually tackle them yourself using proper equipment and procedures. However, if you’re unsure, we offer a virtual inspection service to help you assess the situation.

🧤 Safety Equipment Required

- Respiratory protection: N95 or P100 respirator mask

- Hand protection: Rubber gloves extending to mid-forearm

- Eye protection: Safety goggles

- Body protection: Disposable coveralls

🧽 Cleaning Solutions

- Bleach solution: 1:10 ratio for non-porous surfaces

- White vinegar: Undiluted for porous materials

- Commercial antifungals: EPA-registered products

- Disposal materials: Sealed plastic bags

📋 Step-by-step DIY orange mold removal process for small infestations

Safe DIY Orange Mold Removal Method

Step 1: Isolate Area

Close doors and cover air vents with plastic sheeting to prevent spore spread to clean areas.

Step 2: Protective Equipment

Wear complete protection: N95 respirator, nitrile gloves, eye protection, and disposable coveralls.

Step 3: Prepare Solution

Mix 1:10 bleach ratio for non-porous surfaces or undiluted white vinegar for porous materials.

Step 4: Apply and Wait

Apply solution generously and allow 10-15 minutes contact time for effective mold killing.

Step 5: Scrub Thoroughly

Use disposable materials, working from outside edges toward center to prevent spore spread.

Step 6: Final Treatment

Remove all visible growth, apply solution again, then dry area completely to prevent regrowth.

Step 7: Safe Disposal

Dispose of all cleaning materials in sealed plastic bags and shower immediately after completion.

💡 Important Reminder: DIY removal works only for surface mold on non-porous materials. If contamination involves porous materials like drywall, wood framing, or insulation, professional remediation becomes necessary to prevent incomplete removal and health risks.

🏢 Professional orange mold remediation: When expert intervention protects health and property

Professional orange mold remediation follows strict protocols ensuring complete removal while protecting occupant health and preventing cross-contamination. Certified technicians use industrial-grade equipment and proven methodologies.

🔬 Professional Services Include

- Containment systems: Preventing spore spread

- HEPA filtration: Air purification during remediation

- Antimicrobial treatments: Specialized killing agents

- Moisture correction: Source identification and repair

- Verification testing: Ensuring successful completion

✅ IICRC-Certified Protocols

- Negative air pressure: Controlled containment

- Protective equipment: Professional-grade safety gear

- Disposal procedures: Contaminated material handling

- Documentation: Complete remediation records

- Follow-up testing: Verification of success

IICRC-certified technicians follow established protocols including negative air pressure containment, protective equipment protocols, and disposal procedures for contaminated materials. This systematic approach ensures complete removal while minimizing health risks to occupants during and after remediation.

Mold Busters’ certified remediation specialists provide same-day estimates, comprehensive warranties, and follow-up testing to verify successful completion, ensuring peace of mind for Canadian homeowners facing orange mold challenges.

Orange Mold Prevention in Canadian Homes

Prevention is always better than remediation. Specific strategies for Ontario and Quebec homeowners address seasonal challenges and climate-specific risk factors.

🌸 Spring (Snowmelt Season)

- Basement inspection: Check for water infiltration

- Foundation drainage: Ensure proper water flow away from home

- Roof damage repair: Address ice dam damage promptly

- Increased ventilation: Boost airflow in humid areas

☀️ Summer (High Humidity)

- Dehumidifier use: Maintain 30-50% humidity levels

- Ventilation improvement: Upgrade attic and bathroom fans

- AC maintenance: Address condensation issues

- Window frame inspection: Regular checks for wooden frame damage

🍂 Fall (Preparation)

- Gutter cleaning: Clear debris from gutters and downspouts

- Sealing cracks: Weather-seal around windows and doors

- Pipe insulation: Prevent condensation formation

- Heating service: Prepare systems before winter

❄️ Winter (Monitoring)

- Ice dam prevention: Monitor for formation and address promptly

- Consistent temperature: Maintain stable indoor temperatures

- Exhaust fan use: During cooking and bathing activities

- Condensation checks: Monitor window condensation levels

Expert Orange Mold Services Across Ontario and Quebec

Mold Busters has protected Canadian families from orange mold contamination since 2005, completing over 15,000 inspections and 5,000 successful remediation projects with IICRC-certified specialists.

🔍 Comprehensive Orange Mold Services

- Free virtual inspections for rapid initial assessment

- Laboratory-grade testing with species identification

- Professional remediation following IICRC S520 standards

- Moisture source correction preventing recurrence

- Post-remediation verification ensuring complete removal

- Prevention consulting for long-term protection

⭐ Why Choose Mold Busters for Orange Mold Removal?

🏆 Credentials & Experience

- IICRC-certified mold remediation specialists

- 15+ years serving Ontario and Quebec

- Government-accredited laboratory partnerships

- Advanced diagnostic equipment (thermal imaging, moisture detection)

💰 Service Guarantees

- Same-day reports and detailed estimates

- Comprehensive warranties on all remediation work

- Flexible financing options available

- 24/7 emergency response for urgent situations

Take Immediate Action Against Orange Mold

Orange mold contamination worsens rapidly without professional intervention. Every day of delay increases health risks and remediation costs. Don’t let orange mold compromise your family’s safety or your property’s value.

🚨 Act Now – Orange Mold Emergency Signs

- Strong musty odors throughout your home

- Family respiratory symptoms that are unexplained

- Visible orange growth exceeding 1 square meter

- HVAC system contamination or ductwork growth

- Recent water damage from flooding or leaks

🔍 Free Virtual Inspection

Get expert assessment from the safety of your home. Our certified inspectors provide detailed analysis and immediate recommendations.

📞 Emergency Response

Urgent orange mold situations require immediate professional attention. Our emergency response team provides rapid assessment and containment.

🛡️ Our Orange Mold Removal Guarantee

Mold Busters stands behind every orange mold remediation project with comprehensive warranties and quality guarantees. Our price match guarantee ensures competitive pricing, while our certified technicians provide the highest quality workmanship in the industry.

✅ Quality Guarantee

All work performed to IICRC S520 standards with comprehensive quality assurance protocols.

🛡️ Warranty Protection

Extended warranties on remediation work with ongoing support and monitoring services.

💰 Financial Protection

Flexible financing options and insurance claim assistance available.

🎯 Ready to Eliminate Orange Mold Permanently?

Don’t wait – orange mold health risks increase with exposure time. Contact Mold Busters today for immediate assessment and professional remediation services. Our experts provide same-day responses and customized solutions for every orange mold situation.

Remember: Orange mold identification requires professional expertise. What appears harmless could pose serious health hazards. Trust the certified specialists who have protected Canadian families from mold contamination for over 15 years.

Frequently Asked Questions About Orange Mold

Orange mold can be just as dangerous as black mold, depending on the species. Aspergillus flavus (which can appear orange) produces aflatoxins that are more toxic than the toxins produced by most black molds. The health risk depends on the specific mold species, not just the color.

Yes, orange mold spores can become airborne and spread through HVAC systems, air currents, and on clothing or pets. This is why professional containment is crucial for larger infestations.

Under ideal conditions, orange mold can begin growing within 24-48 hours and become visible within 1-2 weeks. However, mold colonies may remain hidden for months before becoming noticeable.

Coverage varies by policy and cause. Most insurers cover mold remediation if it results from a covered peril (like a burst pipe) but exclude mold from gradual leaks or maintenance issues. Check with your insurance provider for specific coverage details.

Efflorescence appears as white, chalky deposits on masonry surfaces and is caused by salt deposits, not biological growth. Orange mold is fuzzy or velvety, has a musty odor, and grows on organic materials. If you’re unsure, professional testing can provide definitive identification.

✅ Certified Professionals

IICRC-certified mold remediation specialists with 15+ years of experience protecting Canadian families

🔬 Advanced Equipment

State-of-the-art diagnostic tools including thermal imaging, moisture meters, and air quality testing equipment

📋 Comprehensive Service

Complete remediation process from initial inspection through post-remediation verification and prevention consulting

💰 Financial Solutions

Flexible financing options, insurance documentation assistance, and competitive pricing with price match guarantee

📚 Learn More About Mold Types and Prevention

Other Mold Types:

Prevention Resources:

Professional Services:

Disclaimer: This information is provided for educational purposes and should not replace professional assessment. Always consult qualified professionals for safety concerns and health issues related to mold exposure.

Copyright: This content is proprietary and protected by copyright law. Reproduction without permission is prohibited.

References

- Sharma, A., Hazarika, N. K., Barua, P., Shivaprakash, M. R., & Chakrabarti, A. (2013). Acremonium strictum: report of a rare emerging agent of cutaneous hyalohyphomycosis with review of literatures. Mycopathologia, 176(5), 435-441.

- Fakharian, A., Dorudinia, A., Darazam, I. A., Mansouri, D., & Masjedi, M. R. (2015). Acremonium pneumonia: case report and literature review. Tanaffos, 14(2), 156.

- Perdomo, H., Sutton, D. A., García, D., Fothergill, A. W., Cano, J., Gené, J., … & Guarro, J. (2011). Spectrum of clinically relevant Acremonium species in the United States. Journal of Clinical Microbiology, 49(1), 243-256.

- Pitt, J. I., & Hocking, A. D. (2009). The ecology of fungal food spoilage. In Fungi and food spoilage(pp. 3-9). Springer, Boston, MA.

Get Special Gift: Industry-Standard Mold Removal Guidelines

Download the industry-standard guidelines that Mold Busters use in their own mold removal services, including news, tips and special offers:

"*" indicates required fields

Published: February 20, 2019 Updated: August 20, 2025

Written by:

Dusan Sadikovic

Mycologist - MSc, PhD

Mold Busters

Fact checked by:

Michael Golubev

CEO

Mold Busters